Dr.

Adolfo Vásquez Rocca

William

S. Burroughs By Adolfo Vásquez Rocca D.Phil

RESUMEN:

En

la obra de William Burroughs el sujeto se encuentra manipulado y

transformado por los procesos de contagio. El lenguaje es un virus

que se reproduce con gran facilidad y condiciona cualquier actividad

humana, dando cuenta de su intoxicada naturaleza. Los textos de

Burroughs proliferan sin principio ni fin como una plaga, se

reproducen y alargan en sentidos imprevisibles, son el producto de

una hibridación de muy diversos registros que no tienen nada que ver

con una evolución literaria tradicional, sus diferentes elementos

ignoran la progresión de la narración y aparecen a la deriva

desestructurando las novelas de su marco temporal, de su coexistencia

espacial, de su significado, y posibilitando que sea el lector quien

acabe por estructurarlas según sus propios deseos. Ante esta

situación vírica que Burroughs considera que impregna la

existencia, el escritor entiende que nuestro fin es el caos.El caos

como un espacio mítico donde reina lo híbrido, la fusión de lo

contradictorio, el doble monstruoso. La función del caos en la

escritura será una fascinación por los residuos, por el flujo

verbal que nos lleva al hundimiento y a la perdida, por el retorno al

silencio. La aspiración será “Encontrar un lenguaje endémico,

caótico, que sea un lenguaje del cuerpo, que se convierta entonces

en el fin reconocido de la escritura”

Dr.

ADOLFO VÁSQUEZ ROCCA

EL SUJETO DE LAS ADICCIONES

ERRANCIA, La palabra Inconclusa, Nº 9 - 2014, Monográfico –Elsujeto de las adicciones–, Revista de Psicoanálisis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México UNAM.

William

S. Burroughs By Adolfo Vásquez Rocca D.Phil

- Vásquez

Rocca, Adolfo, “William

S. Burroughs y Jacques Derrida; Literatura parasitaria y Cultura

Replicante: Del virus del Lenguaje a la Psicotopografía del Texto”,

En ERRANCIA, La palabra Inconclusa, Nº 9 - 2014, Monográfico –El

sujeto de las adicciones–, Revista de Psicoanálisis, Universidad

Nacional Autónoma de México UNAM.

William

S. Burroughs By Adolfo Vásquez Rocca D.Phil

- VÁSQUEZ

ROCCA, Adolfo, “WILLIAM

S. BURROUGHS Y JACQUES DERRIDA; LITERATURA PARASITARIA Y CULTURA

REPLICANTE: DEL VIRUS DEL LENGUAJE A LA PSICOTOPOGRAFÍA DEL TEXTO”,

En ERRANCIA, La palabra Inconclusa, Nº 9 - 2014, Monográfico –El

sujeto de las adicciones–, Revista de Psicoanálisis, Universidad

Nacional Autónoma de México UNAM.

ERRANCIA

NÚMERO NUEVE

EL

SUJETO DE LAS ADICCIONES

AcademiaEdu

Dr.

Adolfo Vásquez Rocca

William

S. Burroughs By Adolfo Vásquez Rocca D.Phil

"Emitir

no

puede

ser

nunca

mas

que

un

medio

para

emitir

más,

como

la

Droga.

Trate

usted

de

utilizar

la

droga

como

medio

para

otra

cosa

(...)

Al

emisor

no

le

gusta

la

charla.

El

emisor

no

es

un

ser

humano

(...)

Es

el

Virus

Humano."

W.

S.

Burroughs

Desperté

de la Enfermedad a los cuarenta y cinco años, sereno, cuerdo y en

bastante buen estado de salud, a no ser por un hígado algo resentido

y ese aspecto de llevar la carne de prestado que tienen todos los que

sobreviven a la Enfermedad... La mayoría de esos supervivientes no

recuerdan su delirio con detalle. Al parecer, yo tomé notas

detalladas sobre la Enfermedad y el delirio.

W.

S.

Burroughs

La

droga es el producto ideal... la mercancía definitiva. No hace falta

literatura para vender. El cliente se arrastrará por una

alcantarilla para suplicar que le vendan... El comerciante de droga

no vende su producto al consumidor, vende el consumidor a su

producto. No mejora ni simplifica su mercancía. Degrada y simplifica

al cliente. Paga a sus empleados en droga.

W.

S.

Burroughs

La

droga produce una fórmula básica de virus “maligno”: El álgebra

de la necesidad. El rostro del «mal» es siempre el rostro de la

necesidad total. El drogadicto es un hombre con una necesidad

absoluta de droga. A partir de cierta frecuencia, la necesidad no

conoce límite ni control alguno. Con palabras de necesidad total:

«¿Estás dispuesto?» Sí, lo estás. Estás dispuesto a mentir,

engañar, denunciar a tus amigos, robar, hacer lo que sea para

satisfacer esa necesidad total. Porque estarás en un estado de

enfermedad total, de posesión total, imposibilitado para hacer

cualquier otra cosa. Los drogadictos son enfermos que no pueden

actuar más que como actúan. Un perro rabioso no puede sino morder.

Adoptar una actitud puritana no conduce a nada, salvo que se pretenda

mantener el virus en funcionamiento.

W.

S.

Burroughs

William

S. Burroughs By Adolfo Vásquez Rocca D.Phil

AcademiaEdu

Dr.

Adolfo Vásquez Rocca

1.-

La

metáfora

viral.

La

o La obra de William

Burroughs

es un informe sobre sus viajes a un mundo psicodélico y mutante,

donde la condición del hombre está definida por sus adicciones

(tanto al poder como a las drogas) y donde nuestra especie está en

proceso de mutación hacía otra forma poshumana.

William

S. Burroughs fue un sobreviviente. Paranoico y genial. Novelista,

drogadicto e ícono cool. Aunque también su figura ostenta otras

etiquetas: la de padre del punk, la de homosexual, la de pintor, la

de ensayista, la de amante de las armas, la de autor postmodernista,

la de figura primaria de la generación Beat, entre unas cuantas más,

como místico, teórico de los medios, gurú de la ciencia ficción,

etc. Cualquiera de ellas puede funcionar bien como una puerta de

entrada a su mundo.

En

en

la

obra

de

William

Burroughs

el

sujeto

se

encuentra

manipulado

y

transformado

por

los

procesos

de

contagio.

El

lenguaje

es

un

virus

que

se

reproduce

con

gran

facilidad

y

condiciona

cualquier

actividad

humana,

dando

cuenta

de

su

intoxicada

naturaleza.

Los

textos

de

Burroughs

proliferan

sin

principio

ni

fin

como

una

plaga,

se

reproducen

y

alargan

en

sentidos

imprevisibles,

son

el

producto

de

una

hibridación

de

muy

diversos

registros

que

no

tienen

nada

que

ver

con

una

evolución

literaria

tradicional,

sus

diferentes

elementos

ignoran

la

progresión

de

la

narración

y

aparecen

a

la

deriva

desestructurando

las

novelas

de

su

marco

temporal,

de

su

coexistencia

espacial,

de

su

significado,

y

posibilitando

que

sea

el

lector

quien

acabe

por

estructurarlas

según

sus

propios

deseos.

En

el

contexto

de

esta

escritura

laberíntica

en

la

que

corremos

el

riesgo

del

extravío

del

autor

perdido

en

el

texto

o

por

los

constantes

y

expansivos

comentarios,

estamos

ante

la

idea

del

texto

como

tejido

en

perpetuo

urdimiento,

como

un

tejido

que

se

hace,

se

traba

a

sí

mismo

y

deshace

al

sujeto

en

su

textura:

una

araña

tal

que

se

disolvería

ella

misma

en

las

secreciones

constructivas

de

su

tela.

Así

William

Burroughs

viene

a

ser

el

precursor

de

la

deriva,

en

el

sentido

situ

de

dérive

y

en

la

definición

de

Lyotard

de

driftwork.

A

partir

de

los

textos

de

Burroughs

es

posible

prever

una

geografía

enteramente

nueva,

una

especie

de

mapa

de

peregrinaciones

en

el

que

los

lugares

sagrados

se

han

reemplazado

con

experiencias

dromo-literarias:

una

verdadera

ciencia

de

la

psicotopografía.

2.-

Parásitos, lectura deconstructiva e historias de amor triste

Vivimos

un momento no sólo sospechoso sino también generador de otras

tantas incertidumbres, como las que recaen sobre los procesos

significativos. El escepticismo postmoderno, descree radicalmente ya

no –como es obvio– de la verdad, sino de la posibilidad de

interpretaciones validas o más bien validadas de acuerdo a un

criterio externo o distinto a la ficcionalización de los relatos,1

lecturas intencionadas y maliciosas de los textos o –como bien dirá

Derrida– ante sobreinterpretaciones, recuérdese que –“una

buena traducción debe ser abusiva”.2

Las sospechas a este respecto son razonables, si se tiene en cuenta

que la cultura actúa como una cadena de textos que por una parte se

instruyen mutuamente y, por otra, están en desplazamiento

constante.3

La

estrategia de desplazar, diferir, des-estructurar, diseminar, son

propias de una lectura deconstructiva, una lectura –en apariencia–

parasitaria.

La

lectura deconstructiva de una obra dada sería simple y llanamente un

parásito de la lectura obvia o unívoca. Como en el caso de una cita

de una cita como ejemplo del tipo de cadena que pretendemos auscultar

aquí. ¿Es la cita un parásito intruso dentro del cuerpo del texto

principal, o es el texto interpretativo el parásito que rodea y

estrangula a la cita, su anfitrión? El anfitrión alimenta al

parásito y hace posible su vida pero, al mismo tiempo, es aniquilado

por él tal como se acostumbra decir que la crítica mata a la

literatura.4

1A

modo de esbozo de una teoría literaria –de la creación de

entidades ficcionales, mundos y tramas dentro del texto– podemos

caracterizar la naturaleza del relato de ficción como un mundo

posible ceñido a las normas constitutivas de la lógica modal. Este

modelo ofrecerá las respuestas a problemas como la relación entre

el mundo real y el dominio semántico del texto de ficción, o la

posibilidad de hacer declaraciones sobre la función de verdad en

los universos de la ficción.

2DERRIDA,

Jacques, La

deconstrucción en las fronteras de la Filosofía: La retirada de la

metáfora, Editorial

Paidós, Barcelona, 1989.

3VÁSQUEZ

ROCCA, Adolfo, Postmodernidad

y sobreinterpretación. Lecturas paranoicas y métodos obsesivos de

interpretación;

En NÓMADAS. 11 | Enero-Junio.2005. Revista Crítica de Ciencias

Sociales y Jurídicas. UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE

MADRID.http://www.ucm.es/info/nomadas/11/avrocca1.htm

4

MILLER, J. Hillis, "El crítico como

huésped", en Deconstrucción y

crítica, Siglo XXI editores,

México, 2003, p. 211 – 212

Vásquez

Rocca, Adolfo,“William

S. Burroughs y Jacques Derrida; Literatura parasitaria y Cultura

Replicante: Del virus del Lenguaje a la Psicotopografía del Texto”,

En ERRANCIA, La palabra Inconclusa, Nº 9 - 2014

Dr.

Adolfo

Vásquez

Rocca

Adolfo Vásquez Rocca Doctor en Filosofía

Adolfo Vasquez Rocca - Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Doctor en Filosofía Pontificia Universidad

Católica de Valparaíso y Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Profesor de la Escuela de Psicología de la UNAB. –Miembro del

Consejo Editorial Internacional de 'Reflexiones Marginales' –Revista

de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras UNAM. –Miembro del Consejo

Editorial Internacional de Errancia, Revista de Psicoanálisis,

Teoría Crítica y Cultura –UNAM– Universidad Nacional Autónoma

de México. – Director de Revista Observaciones Filosóficas.

Profesor visitante en la Maestría en Filosofía de la Benemérita

Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. –Profesor Asociado al Grupo

Theoria – Proyecto europeo de Investigaciones de Postgrado –UCM.

Eastern Mediterranean University - Academia.edu. Académico

Investigador de la Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Postgrado,

Universidad Andrés Bello. –Investigador Asociado de la Escuela

Matríztica de Santiago –dirigida por el Dr. Humberto Maturana.

Consultor Experto del Consejo Nacional de Innovación para la

Competitividad (CNIC)– Ha publicado el Libro: Peter Sloterdijk;

Esferas, helada cósmica y políticas de climatización, Colección

Novatores, Nº 28, Editorial de la Institución Alfons el Magnànim

(IAM), Valencia, España, 2008. Invitado especial a la

International Conference de la Trienal de Arquitectura de Lisboa |

Lisbon Architecture Triennale 2011.Profesor de Postgrado, Magister en

Biología-Cultural, Escuela Matríztica de Santiago y Universidad

Mayor 2014

Adolfo Vásquez Rocca Arte y Filosofía

Doctor en Filosofía por la Pontificia Universidad

Católica de Valparaíso; Postgrado Universidad Complutense de Madrid,

Departamento de Filosofía IV. Profesor de Postgrado del Instituto de

Filosofía de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso; Profesor

de Antropología y Estética en el Departamento de Artes y Humanidades de

la Universidad Andrés Bello UNAB. Profesor de la Escuela de Periodismo

y Arquitectura UNAB Santiago. – En octubre de 2006 y 2007 es invitado

por la ‘Fundación Hombre y Mundo’ y la UNAM a dictar un Ciclo de

Conferencias en México. – Miembro del Consejo Editorial Internacional

de la ‘Fundación Ética Mundial‘ de México. Director del Consejo Consultivo Internacional de ‘Konvergencias‘, Revista de Filosofía y Culturas en Diálogo, Argentina. Miembro del Conselho Editorial da Humanidades em Revista, Universidade Regional do Noroeste do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil y del Cuerpo Editorial de Sophia –Revista de Filosofía de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador– . Director de Revista Observaciones Filosóficas. Profesor visitante en la Maestría en Filosofía de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. – Profesor visitante Florida Christian University USA y Profesor Asociado al Grupo Theoria –Proyecto europeo de Investigaciones de Postgrado– UCM. Académico Investigador de la Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Postgrado, Universidad Andrés Bello. Artista conceptual. Ha publicado el Libro: Peter Sloterdijk; Esferas, helada cósmica y políticas de climatización,

Colección Novatores, Nº 28, Editorial de la Institución Alfons el

Magnànim (IAM), Valencia, España, 2008. Invitado especial a la

International Conference de la Trienal de Arquitectura de Lisboa | Lisbon Architecture Triennale 2011

Contacto

Web: www.danoex.net/adolfovasquezrocca.html

Academia.edu: emui.academia.edu/AdolfoVasquezRocca

Eastern Mediterranean University

E-mail: adolfovrocca@gmail.com

Linkedin: linkedin.com/pub/adolfo-vasquez-rocca/25/502/21a

Academia.edu: emui.academia.edu/AdolfoVasquezRocca

Eastern Mediterranean University

E-mail: adolfovrocca@gmail.com

Linkedin: linkedin.com/pub/adolfo-vasquez-rocca/25/502/21a

Domicilio

Valparaíso,

Chile

Adscripción Académica

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso

Universidad Andrés Bello UNAB

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Eastern Mediterranean University - Academia.edu

Universidad Andrés Bello UNAB

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Eastern Mediterranean University - Academia.edu

Trayectoria Académica

Doctor

en Filosofía por la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso;

Postgrado Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Departamento de Filosofía

IV, mención Filosofía Contemporánea y Estética.

Profesor de Postgrado del Instituto de Filosofía de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso; Profesor de Antropología y Estética en el Departamento de Artes y Humanidades de la Universidad Andrés Bello UNAB. Profesor de la Escuela de Periodismo, Profesor Adjunto Escuela de Psicología y de la Facultad de Arquitectura UNAB Santiago. Profesor PEL Programa Especial de Licenciatura en Diseño, UNAB – DUOC UC.

En octubre de 2006 y 2007 es invitado por la 'Fundación Hombre y Mundo' y la UNAM a dictar un Ciclo de Conferencias en México.

Miembro del Consejo Editorial Internacional de la 'Fundación Ética Mundial' de México. Director del Consejo Consultivo Internacional de 'Konvergencias', Revista de Filosofía y Culturas en Diálogo, Argentina. Miembro del Consejo Editorial Internacional de Revista Praxis. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Nacional UNA, Costa Rica. Miembro del Conselho Editorial da Humanidades em Revista, Universidade Regional do Noroeste do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil y del Cuerpo Editorial de Sophia –Revista de Filosofía de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador–. –Secretario Ejecutivo de Revista Philosophica PUCV.

Asesor Consultivo de Enfocarte –Revista de Arte y Literatura– Cataluña / Gijón, Asturias, España. –Miembro del Consejo Editorial Internacional de 'Reflexiones Marginales' –Revista de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras UNAM. –Editor Asociado de Societarts, Revista de artes y humanidades, adscrita a la Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. –Miembro del Comité Editorial de International Journal of Safety and Security in Tourism and Hospitality, publicación científica de la Universidad de Palermo. –Miembro Titular del Consejo Editorial Internacional de Errancia, Revista de Psicoanálisis, Teoría Crítica y Cultura –UNAM– Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. –Miembro del Consejo Editorial de Revista “Campos en Ciencias Sociales”, Universidad Santo Tomás © , Bogotá, Colombia.

Miembro de la Federación Internacional de Archivos Fílmicos (FIAF) con sede en Bruselas, Bélgica. Director de Revista Observaciones Filosóficas. Profesor visitante en la Maestría en Filosofía de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. – Profesor visitante Florida Christian University USA y Profesor Asociado al Grupo Theoria – Proyecto europeo de Investigaciones de Postgrado –UCM. Eastern Mediterranean University - Academia.edu. Académico Investigador de la Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Postgrado, Universidad Andrés Bello. –Investigador Asociado y Profesor adjunto de la Escuela Matríztica de Santiago –dirigida por el Dr. Humberto Maturana. Consultor Experto del Consejo Nacional de Innovación para la Competitividad (CNIC)– Artista conceptual. Crítico de Arte. Ha publicado el Libro: Peter Sloterdijk; Esferas, helada cósmica y políticas de climatización, Colección Novatores, Nº 28, Editorial de la Institución Alfons el Magnànim (IAM), Valencia, España, 2008. Invitado especial a la International Conference de la Trienal de Arquitectura de Lisboa | Lisbon Architecture Triennale 2011. Traducido al Francés - Publicado en la sección Architecture de la Anthologie: Le Néant Dans la Pensée Contemporaine . Publications du Centre Français d'Iconologie Comparée CFIC, Bès Editions , París, © 2012. Profesor de Postgrado, Magister en Biología-Cultural, Escuela Matríztica de Santiago y Universidad Mayor 2013.- 2014

Profesor de Postgrado del Instituto de Filosofía de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso; Profesor de Antropología y Estética en el Departamento de Artes y Humanidades de la Universidad Andrés Bello UNAB. Profesor de la Escuela de Periodismo, Profesor Adjunto Escuela de Psicología y de la Facultad de Arquitectura UNAB Santiago. Profesor PEL Programa Especial de Licenciatura en Diseño, UNAB – DUOC UC.

En octubre de 2006 y 2007 es invitado por la 'Fundación Hombre y Mundo' y la UNAM a dictar un Ciclo de Conferencias en México.

Miembro del Consejo Editorial Internacional de la 'Fundación Ética Mundial' de México. Director del Consejo Consultivo Internacional de 'Konvergencias', Revista de Filosofía y Culturas en Diálogo, Argentina. Miembro del Consejo Editorial Internacional de Revista Praxis. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Nacional UNA, Costa Rica. Miembro del Conselho Editorial da Humanidades em Revista, Universidade Regional do Noroeste do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil y del Cuerpo Editorial de Sophia –Revista de Filosofía de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador–. –Secretario Ejecutivo de Revista Philosophica PUCV.

Asesor Consultivo de Enfocarte –Revista de Arte y Literatura– Cataluña / Gijón, Asturias, España. –Miembro del Consejo Editorial Internacional de 'Reflexiones Marginales' –Revista de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras UNAM. –Editor Asociado de Societarts, Revista de artes y humanidades, adscrita a la Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. –Miembro del Comité Editorial de International Journal of Safety and Security in Tourism and Hospitality, publicación científica de la Universidad de Palermo. –Miembro Titular del Consejo Editorial Internacional de Errancia, Revista de Psicoanálisis, Teoría Crítica y Cultura –UNAM– Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. –Miembro del Consejo Editorial de Revista “Campos en Ciencias Sociales”, Universidad Santo Tomás © , Bogotá, Colombia.

Miembro de la Federación Internacional de Archivos Fílmicos (FIAF) con sede en Bruselas, Bélgica. Director de Revista Observaciones Filosóficas. Profesor visitante en la Maestría en Filosofía de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. – Profesor visitante Florida Christian University USA y Profesor Asociado al Grupo Theoria – Proyecto europeo de Investigaciones de Postgrado –UCM. Eastern Mediterranean University - Academia.edu. Académico Investigador de la Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Postgrado, Universidad Andrés Bello. –Investigador Asociado y Profesor adjunto de la Escuela Matríztica de Santiago –dirigida por el Dr. Humberto Maturana. Consultor Experto del Consejo Nacional de Innovación para la Competitividad (CNIC)– Artista conceptual. Crítico de Arte. Ha publicado el Libro: Peter Sloterdijk; Esferas, helada cósmica y políticas de climatización, Colección Novatores, Nº 28, Editorial de la Institución Alfons el Magnànim (IAM), Valencia, España, 2008. Invitado especial a la International Conference de la Trienal de Arquitectura de Lisboa | Lisbon Architecture Triennale 2011. Traducido al Francés - Publicado en la sección Architecture de la Anthologie: Le Néant Dans la Pensée Contemporaine . Publications du Centre Français d'Iconologie Comparée CFIC, Bès Editions , París, © 2012. Profesor de Postgrado, Magister en Biología-Cultural, Escuela Matríztica de Santiago y Universidad Mayor 2013.- 2014

Publicaciones

- Ver todas las publicaciones →

(2014)

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, "Lógica

paraconsistente, paradojas y lecturas parasitarias: Del virus del

lenguaje a las lógicas difusas, (Lewis Carroll, B. Russell, K. Gödel y

W. S. Burroughs)", En EIKASIA, Revista de Filosofía, Nº 58 – 2014, Sociedad Asturiana de Filosofía SAF, Oviedo, España, pp. 41– 64.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Nietzsche y Freud, negociación, culpa y crueldad: las pulsiones y sus destinos, eros y thanatos (agresividad y destructividad)”, En EIKASIA Nº 57, 2014, Revista de Filosofía, Oviedo, SAF - Sociedad Asturiana de Filosofía.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, "Sloterdijk: el retorno de la religión, la lucha de los monoteísmos históricos y el asedio a jerusalén; Psicopolítica de los bancos de ira, apocalipsis y relatos escatológicos; del fundamentalismo islámico a los espectros de Marx". En Revista Almiar - III Época Nº 75 - 2014, ISSN: 1696-4807, MARGEN CERO, Madrid.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Freud y Kafka: Criminales por sentimiento de culpabilidad: En torno a la crueldad, el sabotaje y la auto-destructividad humana”, En EIKASIA, Revista de la Sociedad Asturiana de Filosofía SAF, Nº 55 – marzo, 2014 - ISSN 1885-5679 – Oviedo, España, pp. 73 – 92.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Zoología Política: Disturbios en el Parque Humano, Cultura de Masas y el modelo amigable de la Sociedad Literaria”, En Revista Almiar, MARGEN CERO, Madrid, III Época – Nº 73 marzo–abril, 2014.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Peter Sloterdijk: Constitución Psico-inmunitaria de la naturaleza humana, Ciencia Zoológica y Ciencia Pneumática; Deriva biotecnológica e historia espiritual de la criatura”, En Academia.edu, Manuscritos Transversales, 2014, pp. 45–66; y Cuaderno de Materiales, ISSN: 1139-4382, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Nº 26, 2014.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Nietzsche y Freud, negociación, culpa y crueldad: las pulsiones y sus destinos, eros y thanatos (agresividad y destructividad)”, En EIKASIA Nº 57, 2014, Revista de Filosofía, Oviedo, SAF - Sociedad Asturiana de Filosofía.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, "Sloterdijk: el retorno de la religión, la lucha de los monoteísmos históricos y el asedio a jerusalén; Psicopolítica de los bancos de ira, apocalipsis y relatos escatológicos; del fundamentalismo islámico a los espectros de Marx". En Revista Almiar - III Época Nº 75 - 2014, ISSN: 1696-4807, MARGEN CERO, Madrid.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Freud y Kafka: Criminales por sentimiento de culpabilidad: En torno a la crueldad, el sabotaje y la auto-destructividad humana”, En EIKASIA, Revista de la Sociedad Asturiana de Filosofía SAF, Nº 55 – marzo, 2014 - ISSN 1885-5679 – Oviedo, España, pp. 73 – 92.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Zoología Política: Disturbios en el Parque Humano, Cultura de Masas y el modelo amigable de la Sociedad Literaria”, En Revista Almiar, MARGEN CERO, Madrid, III Época – Nº 73 marzo–abril, 2014.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Peter Sloterdijk: Constitución Psico-inmunitaria de la naturaleza humana, Ciencia Zoológica y Ciencia Pneumática; Deriva biotecnológica e historia espiritual de la criatura”, En Academia.edu, Manuscritos Transversales, 2014, pp. 45–66; y Cuaderno de Materiales, ISSN: 1139-4382, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Nº 26, 2014.

(2013)

Vásquez

Rocca, Adolfo, "Arte

Conceptual y Posconceptual. La idea como arte: Duchamp, Beuys, Cage y

Fluxus",

En NÓMADAS, Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas -

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID, Nómadas Nº 37 |

Enero-Junio 2013 (I), pp. 100 -

130.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Peter Sloterdijk: El animal acrobático, prácticas antropotécnicas y diseño de lo humano”, En NÓMADAS, Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas - UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID, NÓMADAS. Nº 39 | Julio-Diciembre, 2013 (I) pp. 100-125.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, " Foucault; 'Los Anormales', una Genealogía de lo Monstruoso; Apuntes para una Historiografía de la Locura.", En NÓMADAS, Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas - UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID, —NÓMADAS. Nº 34 – 2012 (2), pp. 403 - 420

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, "Sloterdijk: Neuroglobalización, estresores y prácticas psico-inmunológicas", En NÓMADAS, Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas - UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID, Nómadas Nº 35 | Julio-Diciembre.2012 - 2013 (I), pp. 427 - 457

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Peter Sloterdijk: Experimentos con uno mismo. Ensayos de intoxicación voluntaria y constitución psicoinmunitaria de la naturaleza humana”, REVISTA DE ANTROPOLOGÍA EXPERIMENTAL, Nº 13, 2013 - pp. 323-340 - ISSN: 1578-4282, UNIVERSIDAD DE JAÉN (España).

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, "Peter Sloterdijk: Celo de Dios, neo-expresionismo islámico y política exterior norteamericana", EIKASIA, Revista de la Sociedad Asturiana de Filosofía SAF, Nº 53 – diciembre, 2013 - ISSN 1885-5679 – Oviedo, España, pp. 23 – 40.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Peter Sloterdijk: El animal acrobático, prácticas antropotécnicas y diseño de lo humano”, En NÓMADAS, Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas - UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID, NÓMADAS. Nº 39 | Julio-Diciembre, 2013 (I) pp. 100-125.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, " Foucault; 'Los Anormales', una Genealogía de lo Monstruoso; Apuntes para una Historiografía de la Locura.", En NÓMADAS, Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas - UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID, —NÓMADAS. Nº 34 – 2012 (2), pp. 403 - 420

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, "Sloterdijk: Neuroglobalización, estresores y prácticas psico-inmunológicas", En NÓMADAS, Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas - UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID, Nómadas Nº 35 | Julio-Diciembre.2012 - 2013 (I), pp. 427 - 457

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Peter Sloterdijk: Experimentos con uno mismo. Ensayos de intoxicación voluntaria y constitución psicoinmunitaria de la naturaleza humana”, REVISTA DE ANTROPOLOGÍA EXPERIMENTAL, Nº 13, 2013 - pp. 323-340 - ISSN: 1578-4282, UNIVERSIDAD DE JAÉN (España).

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, "Peter Sloterdijk: Celo de Dios, neo-expresionismo islámico y política exterior norteamericana", EIKASIA, Revista de la Sociedad Asturiana de Filosofía SAF, Nº 53 – diciembre, 2013 - ISSN 1885-5679 – Oviedo, España, pp. 23 – 40.

Libros

Libro: Peter

Sloterdijk; Esferas, helada cósmica y políticas de climatización,

Colección Novatores, Nº 28, Editorial de la Institución Alfons el

Magnànim (IAM), Valencia, España, 2008. 221 páginas | I.S.B.N.: 978-84-7822-523-1

Libro: Rorty: el Giro narrativo de la Ética o la Filosofía como género literario [Compilación de Conferencias en México D.F.] Editorial Hombre y Mundo (H & M), México, 2009, 450 páginas I.S.B.N.: 978-3-7800-520-1

Libro: Rorty: el Giro narrativo de la Ética o la Filosofía como género literario [Compilación de Conferencias en México D.F.] Editorial Hombre y Mundo (H & M), México, 2009, 450 páginas I.S.B.N.: 978-3-7800-520-1

DOAJ → Directory of Open Access Journals

DIALNET → Directorio de Publicaciones Científicas Hispanoamericanas

Publications Scientific →

Biblioteket og Aarhus Universitet, Denmark | Det Humanistiske Fakultet →

Biblioteca Universia → Unesco - CSIC

Biblioteca UCM → Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Biblioteca Asociación Filosófica UI →

Eastern Mediterranean University - Academia.edu

Publicaciones Indexadas en Revista Nómadas

VÁSQUEZ ROCCA, Adolfo, "SLOTERDIJK: NEUROGLOBALIZACIÓN, ESTRESORES Y PRÁCTICAS PSICO-INMUNOLÓGICAS",

En NÓMADAS, Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas -

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID, Nómadas Nº 35 | Julio-Diciembre.2012 -

2013 (I), pp. 427 - 457http://www.theoria.eu/nomadas/35/adolfovrocca.pdf

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Peter

Sloterdijk: Experimentos con uno mismo. Ensayos de intoxicación

voluntaria y constitución psicoinmunitaria de la naturaleza humana”, En ARTEFACTO -Pensamientos sobre la Técnica- UBA, abril, 2013

http://www.revista-artefacto.com.ar/pdf_textos/84.pdf

http://www.revista-artefacto.com.ar/pdf_textos/84.pdf

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Sloterdijk:

La Comuna Exhalada, hacia una Filosofía de la levedad. La Escena

Originaria de la tradición judeocristiana: La creación del hombre”, En Espiral Nº 44 - 2013, Revista de Cultura y Pensamiento Contemporáneo, Tijuana, BC. México.

http://www.revistaespiral.org/espiral_44/filosofia_adolfo.html

http://www.revistaespiral.org/espiral_44/filosofia_adolfo.html

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Nietzsche:

De la voluntad de ficción a la voluntad de poder; Aproximación

estético-epistemológica a la concepción biológica de lo literario”, En ROSEBUD – Critica, scrittura, giornalismo online - Anno III, DUBLIN, IRELAND, Septiembre, 2013.

http://rinabrundu.com/2013/09/04/nietzsche-de-la-voluntad-de-ficcion-a-la-voluntad-de-poder-aproximacion-estetico-epistemologica-a-la-concepcion-biologica-de-lo-literario/

http://rinabrundu.com/2013/09/04/nietzsche-de-la-voluntad-de-ficcion-a-la-voluntad-de-poder-aproximacion-estetico-epistemologica-a-la-concepcion-biologica-de-lo-literario/

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Peter Sloterdijk: El animal acrobático, prácticas antropotécnicas y diseño de lo humano”,

En NÓMADAS, Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas -

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID, NÓMADAS. Nº 39 | Julio-Diciembre,

2013 (I) pp. 100-125

http://pendientedemigracion.ucm.es/info/nomadas/39/adolfovrocca_es.pdf

http://pendientedemigracion.ucm.es/info/nomadas/39/adolfovrocca_es.pdf

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “Peter

Sloterdijk: Experimentos con uno mismo. Ensayos de intoxicación

voluntaria y constitución psicoinmunitaria de la naturaleza humana”, REVISTA DE ANTROPOLOGÍA EXPERIMENTAL, Nº 13, 2013 - pp. 323-340 - ISSN: 1578-4282, UNIVERSIDAD DE JAÉN (España).

http://www.ujaen.es/huesped/rae/articulos2013/21vasquez13.pdf

http://www.ujaen.es/huesped/rae/articulos2013/21vasquez13.pdf

Adolfo Vásquez Rocca Doctor en Filosofía

ADOLFO VÁSQUEZ ROCCA PH.D. - CURRICULUM ACADÉMICO

Eastern Mediterranean University - Academia.edu

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Universidad Andrés Bello UNAB

E-mail: adolfovrocca@gmail.com

PAPELES___ MANUSCRITOS___DIARIOS__TESIS ___CUADERNOS __BORRADORES Y PRÓLOGOS___FILOSOFÍA, ARTE Y NOTAS AL MARGEN ___DR. ADOLFO VÁSQUEZ ROCCA

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, "Lógica paraconsistente, paradojas y lecturas parasitarias: Del virus del lenguaje a las lógicas difusas, (Lewis Carroll, B. Russell, K. Gödel y W. S. Burroughs)", En EIKASIA, Revista de Filosofía, Nº 58 – 2014, Sociedad Asturiana de Filosofía SAF, Oviedo, España, pp. 41– 64.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “William Burroughs: Literatura ectoplasmoide y mutaciones antropológicas. Del virus del lenguaje a la psicotopografía del texto”,

En NÓMADAS, Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas -

Universidad Complutense de Madrid, NÓMADAS. 26 | Enero-Junio.2010 (II),

pp. 251-265. http://www.ucm.es/info/nomadas/26/avrocca2.pdf

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, "La Metáfora Viral en William Burroughs; Postmodernidad, compulsión y

Literatura conspirativa"

En Qì Revista de pensamiento cultura y

creación, Año VII – Nº8, 2006, pp. 118 a 124,

UNIVERSIDAD CARLOS III DE MADRID (ESPAÑA, UE)http://www.margencero.com/articulos/new03/burroughs.html

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, "W. Burroughs; La metáfora viral y sus mutaciones antropológicas"

En Almiar MARGEN CERO, Revista Fundadora de la ASOCIACIÓN DE

REVISTAS DIGITALES DE ESPAÑA - Nº 46 - 2009.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “William Burroughs. Metáfora Viral, compulsión y Literatura conspirativa”, En NÓMADAS, Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas - UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID, NÓMADAS.13 | Enero-Junio (2006.1) pp. 419-424

http://pendientedemigracion.ucm.es/info/nomadas/13/avrocca2.pdf

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, “La Metáfora Viral en William Burroughs; Posmodernidad, compulsión y Literatura conspirativa”, en NÓMADAS, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Nº 13 (2006.1), p. 419-424, Versión digital: <http://revistas.ucm.es/cps/15786730/articulos/NOMA0606120419A.PDF>

Y En Qì Revista de pensamiento cultura y creación, Año VII – Nº 8, 2006, pp. 118 a 124, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid.

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo, "W. Burroughs; La metáfora viral y sus mutaciones antropológicas"

En Almiar MARGEN CERO, Revista Fundadora de la ASOCIACIÓN DE

REVISTAS DIGITALES DE ESPAÑA - Nº 46 - 2009.

William

S. Burroughs By Adolfo Vásquez Rocca D.Phil

BEAT WRITER'S GOT THE BEAT: William S. Burroughs Sings!

One of

the most unlikely stars of the late '70s-to-early '90s punk/college rock

days wasn't a musician at all, but a taciturn, elderly writer clad not

in flannel shirts and Doc Martens, but a three-piece suit, hat, and

cane. How a novelist with no musical background who began his career in

the 1940s became so popular an alternative music figure that Kurt

Cobaine backed him up on one of Cobain's last recordings is one

of the odder, more fascinating footnotes in this

otherwise heavily examined musical era.

William

S. Burroughs is, of course, one of the most celebrated figures in 20th

century literature due to his key participation in the "Beat" movement

that essentially dragged American letters into the modern era, rejecting

classical European/Shakespearean influences in an attempt to create a

literature as unique to the U.S. as jazz is to American music. And,

indeed, the cliche of the beatnik reciting stream-of-consciousness

poetry over cool jazz is the first thing that pops to mind when

considering the confluence of the Beats with music.

William

S. Burroughs is, of course, one of the most celebrated figures in 20th

century literature due to his key participation in the "Beat" movement

that essentially dragged American letters into the modern era, rejecting

classical European/Shakespearean influences in an attempt to create a

literature as unique to the U.S. as jazz is to American music. And,

indeed, the cliche of the beatnik reciting stream-of-consciousness

poetry over cool jazz is the first thing that pops to mind when

considering the confluence of the Beats with music.

But Burroughs was never a beatnik. He was a junkie and heroin dealer who accidentally shot and killed his wife, traveled thru Latin America and Morocco, helped popularize North African trance ritual music, dismantled literature via his "cut-up" method of chopping up and rearranging pages of writings, was put on trial for obscenity, saw his son go to prison, saw his son die, was gay in the pre-Stonewall days, and co-created a "dream machine" said to create somewhat hallucinatory experiences when activated.

In other words, he'd been thru some shit. By the late '70s, he was back in the States and started giving public readings in his now impossibly craggy, deep, world-weary voice. This was to be his main source of income for the last years of his life. The downtown New York scene was receptive to both his writings and his voice, filled as it was with not only the weight and wisdom of a life you never led, but with an idiosyncratic rhythmic delivery. He left New York for Kansas in 1981, well on his way to becoming an icon of cool.

After a while, it wasn't enough to just listen to Burroughs read his own works, with increasingly elaborate musical backings, but to hire him to perform on other people's recordings. And that is what we have here: not Burroughs' own releases, but his various miscellaneous appearances on other bands' songs. Having Burroughs perform your music gave you instant hip cred, and gave a Bill a paycheck. As this article puts it, he was a rock star to rock stars. William S. Burroughs died in 1997, at age 83.

William S. Burroughs Sings

UPDATE 10/13: Also now up on ubu.web: http://www.ubu.com/sound/burroughs_sings.html

1. Star Me Kitten (with REM, from "Songs in the Key of X: Music from and Inspired by 'the X-Files'" - 1996)

2. Is Everybody In? (with The Doors, reciting Jim Morrison poetry, from "Stoned Immaculate: The Music of the Doors")

3. Sharkey's Night (with Laurie Anderson, from "Mister Heartbreak" - 1983)

4. What Keeps Mankind Alive (from Kurt Weill tribute album "September Songs")

5. 'T 'Aint No Sin (1920s jazz song, performed on Tom Waits' "The Black Rider" - 1993)

6. Quick Fix (w/Ministry, "Just One Fix" b-side - 1992)

7. Old Lady Sloan (w/The Eudoras, covering a song by a Lawrence, Kansas punk band from "The Mortal Micronotz Tribute!" - 1995

8. Ich Bin Von Kopf Bis Fub Auf Liebe Eingestellt (Falling In Love Again) - Marlene Deitrich cover, from "Dead City Radio" - 1988

William

S. Burroughs is, of course, one of the most celebrated figures in 20th

century literature due to his key participation in the "Beat" movement

that essentially dragged American letters into the modern era, rejecting

classical European/Shakespearean influences in an attempt to create a

literature as unique to the U.S. as jazz is to American music. And,

indeed, the cliche of the beatnik reciting stream-of-consciousness

poetry over cool jazz is the first thing that pops to mind when

considering the confluence of the Beats with music.

William

S. Burroughs is, of course, one of the most celebrated figures in 20th

century literature due to his key participation in the "Beat" movement

that essentially dragged American letters into the modern era, rejecting

classical European/Shakespearean influences in an attempt to create a

literature as unique to the U.S. as jazz is to American music. And,

indeed, the cliche of the beatnik reciting stream-of-consciousness

poetry over cool jazz is the first thing that pops to mind when

considering the confluence of the Beats with music.But Burroughs was never a beatnik. He was a junkie and heroin dealer who accidentally shot and killed his wife, traveled thru Latin America and Morocco, helped popularize North African trance ritual music, dismantled literature via his "cut-up" method of chopping up and rearranging pages of writings, was put on trial for obscenity, saw his son go to prison, saw his son die, was gay in the pre-Stonewall days, and co-created a "dream machine" said to create somewhat hallucinatory experiences when activated.

In other words, he'd been thru some shit. By the late '70s, he was back in the States and started giving public readings in his now impossibly craggy, deep, world-weary voice. This was to be his main source of income for the last years of his life. The downtown New York scene was receptive to both his writings and his voice, filled as it was with not only the weight and wisdom of a life you never led, but with an idiosyncratic rhythmic delivery. He left New York for Kansas in 1981, well on his way to becoming an icon of cool.

After a while, it wasn't enough to just listen to Burroughs read his own works, with increasingly elaborate musical backings, but to hire him to perform on other people's recordings. And that is what we have here: not Burroughs' own releases, but his various miscellaneous appearances on other bands' songs. Having Burroughs perform your music gave you instant hip cred, and gave a Bill a paycheck. As this article puts it, he was a rock star to rock stars. William S. Burroughs died in 1997, at age 83.

William S. Burroughs Sings

UPDATE 10/13: Also now up on ubu.web: http://www.ubu.com/sound/burroughs_sings.html

1. Star Me Kitten (with REM, from "Songs in the Key of X: Music from and Inspired by 'the X-Files'" - 1996)

2. Is Everybody In? (with The Doors, reciting Jim Morrison poetry, from "Stoned Immaculate: The Music of the Doors")

3. Sharkey's Night (with Laurie Anderson, from "Mister Heartbreak" - 1983)

4. What Keeps Mankind Alive (from Kurt Weill tribute album "September Songs")

5. 'T 'Aint No Sin (1920s jazz song, performed on Tom Waits' "The Black Rider" - 1993)

6. Quick Fix (w/Ministry, "Just One Fix" b-side - 1992)

7. Old Lady Sloan (w/The Eudoras, covering a song by a Lawrence, Kansas punk band from "The Mortal Micronotz Tribute!" - 1995

8. Ich Bin Von Kopf Bis Fub Auf Liebe Eingestellt (Falling In Love Again) - Marlene Deitrich cover, from "Dead City Radio" - 1988

William

S. Burroughs By Adolfo Vásquez Rocca D.Phil

William

S. Burroughs By Adolfo Vásquez Rocca D.Phil

Sobrevivió

a todo: a Jack Kerouac y Allen Ginsberg, a sus propios excesos de

todo tipo, a la culpa, a los exilios, a los críticos. El sábado lo

mató su corazón, a los 83, en Kansas City.

Aunque

las informaciones cablegráficas repitan que murió el sábado, a los

83 años, en un cuarto de hospital de Lawrence (Kansas), los lectores

de William S. Burroughs harán bien en desconfiar. Beatnik

heterodoxo, perverso polimorfo, gourmet entusiasta de todas las

estimulaciones del mundo, el escritor sobrevivió a demasiadas

catástrofes como para que un módico ataque cardíaco obligue a

escribir sobre él en pasado.

Burroughs sobrevivió a una extensa carrera de heroinómano, emprendida intencionalmente a principios de los años '40, cuando dejó su St. Louis natal y desembarcó en Nueva York, y sólo interrumpida 20 años más tarde, en una diminuta habitación de Tánger cuando, después de pasarse un mes contemplándose su propio pie, descubrió, también intencionalmente, que se estaba muriendo. Sobrevivió a una fugaz experiencia criminal en México, cuando puso en práctica su alucinada puntería de Guillermo Tell con su mujer, Joan Vollmer Adams, y la mató con el disparo destinado al vaso de vidrio que había puesto sobre su cabeza. Sobrevivió a la culpa, al exilio (Sudamérica, Tánger) y a los procesos judiciales que le deparó a fines de los '50 su novela más famosa, Almuerzo desnudo, el más eufórico descenso a los infiernos de la droga que la

Sobrevivió a la admirada envidia que le profesaron Jack Kerouac y Allen Ginsberg, los dos cómplices con los que fundó el movimiento beatnik. Sobrevivió a la policía, a los médicos, al anonimato y a la fama, y hasta sobrevivió a Kurt Cobain, que en 1992 lo convocó para grabar su voz mitológica en un tema del álbum The Priest They Called Him. Ironías de la literatura: en 1993, Christopher Silvester, profético editor de una antología de reportajes, concluye el prólogo a la entrevista de Burroughs dándolo por muerto... en 1996.

Esa extraordinaria voluntad de persistencia es apenas la cara visible de la energía que consumió la vida y la obra de Burroughs: la energía de experimentar. Con su propio cuerpo, con la literatura, con la tecnología (no en vano Burroughs, ese Marshall Macluhan políticamente incorrecto, era nieto del inventor de la máquina de calcular), con las formas monstruosas que empieza a asumir el mundo contemporáneo. Ya en sus primeros libros (Yonqui y Queer, de principios de los años '50) aparece trazada la prodigiosa continuidad entre experiencia y ficción que marcaría toda su carrera. En 1959 publicó Almuerzo desnudo, la perfecta autobiografía de un heroinómano: libro radical, una biblia atroz que expande límites sin pudor y sin la menor sombra de autocompasión. Los temas: droga y sexualidad, la aleación que lo cubriría de escarnio y de prestigio. Las formas: una escritura salvaje, de una nitidez casi clínica, experta en el montaje de géneros, materiales y texturas que la literatura pocas veces se había atrevido a hacer coexistir. Este gran libro de drogón es también un gran libro de vidente que anuncia el mundo del porvenir. Un paisaje de paranoia y control planetarios.

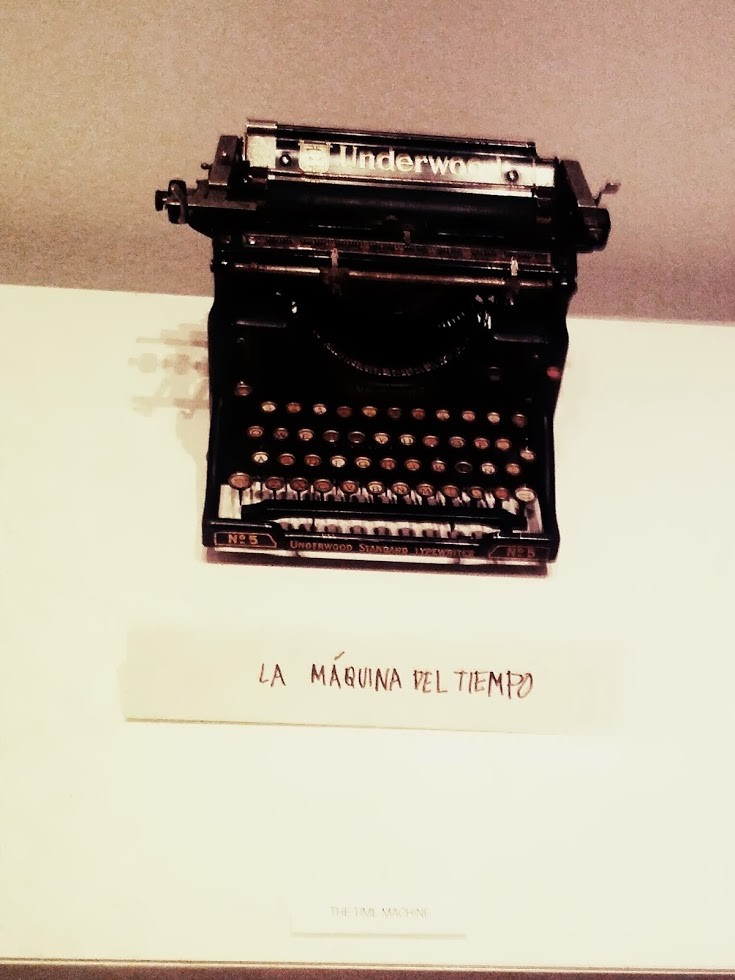

Con Almuerzo desnudo nació el mito Burroughs. El resto de su obra es vasto, intrincado, a menudo ilegible. Libros como La máquina blanda, El boleto que explotó (próximo a aparecer en castellano) o Expreso Nova son nuevos atajos de un camino sin retorno, solitario y encarnizado, donde la experiencia estalla en jirones casi irreconocibles. La herencia Burroughs, sin embargo, no es libresca. Leída o no, conocida o rozada de segunda mano, su prosa y su figura fermentan desde hace décadas en los márgenes del mundo literario: en el rock (Patti Smith, Lou Reed, Soft Machine y David Bowie son algunos de sus deudores reconocidos, esto sin mencionar que U2 lo homenajea en su último video "Last nigth on heart"), en el cine (la versión Cronenberg de Almuerzo desnudo, el gurú adicto que Burroughs interpreta en Drugstore Cowboy, de Gus Van Sant), en todas aquellas regiones de la experiencia donde la vida busca transformarse en otra cosa.

William

S. Burroughs By Adolfo Vásquez Rocca D.Phil

PRECEDIENDO AL “BEAT”: SU PRIMERA NOVELA

EL NACIMIENTO DEL MUTANTE Y SU ALMUERZO DESNUDO

DE LOS SESENTA A LOS NOVENTA, O EL TRIUNFO DEL CUT-UP

William S. Burroughs By Adolfo Vásquez Rocca D.Phil

AcademiaEdu

Vásquez Rocca, Adolfo,“William S. Burroughs y Jacques Derrida; Literatura parasitaria y Cultura Replicante: Del virus del Lenguaje a la Psicotopografía del Texto”, En ERRANCIA, La palabra Inconclusa, Nº 9 - 2014

William S. Burroughs By Adolfo Vásquez Rocca D.Phil

William S. Burroughs

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other people named William Burroughs, see William Burroughs (disambiguation).

| William S. Burroughs | |

|---|---|

|

Burroughs

| |

| Born | William Seward Burroughs II February 5, 1914 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | August 2, 1997 (aged 83) Lawrence, Kansas, U.S. |

| Pen name | William Lee |

| Occupation | Author |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Genre | Satire, paranoid fiction |

| Literary movement | Beat Generation, Postmodernism |

| Notable works | Naked Lunch (1959) |

| Spouse | Ilse von Klapper (1937–1946) Joan Vollmer (1946–1951) |

| Children | William S. Burroughs, Jr. |

| Relatives | William Seward Burroughs I, grandfather Ivy Lee, maternal uncle |

|

|---|

| William S. Burroughs By Adolfo Vásquez Rocca D.Phil |

|---|

| Signature |

|---|

He was born to a wealthy family in St. Louis, Missouri, grandson of the inventor and founder of the Burroughs Corporation, William Seward Burroughs I, and nephew of public relations manager Ivy Lee. Burroughs began writing essays and journals in early adolescence. He left home in 1932 to attend Harvard University, studied English, and anthropology as a postgraduate, and later attended medical school in Vienna. After being turned down by the Office of Strategic Services and U.S. Navy

in 1942 to serve in World War II, he picked up the drug addiction that

affected him for the rest of his life, while working a variety of jobs.

In 1943 while living in New York City, he befriended Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, the mutually influential foundation of which grew into the Beat Generation, and later the 1960s counterculture.

Much of Burroughs's work is semi-autobiographical, primarily drawn from his experiences as a heroin addict, as he lived throughout Mexico City, London, Paris, Berlin, the South American Amazon and Tangier in Morocco. Burroughs accidentally killed his second wife, Joan Vollmer, in 1951 in Mexico City, and was consequently convicted of manslaughter. In the introduction to Queer,

a novel written in 1953 but not published until 1985, Burroughs states,

"I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would have never become

a writer but for Joan’s death ... [S]o the death of Joan brought me

into contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a

lifelong struggle, in which I had no choice except to write my way

out". (Queer, 1985, p.xxii). Finding success with his confessional first novel, Junkie (1953), Burroughs is perhaps best known for his third novel Naked Lunch (1959), a controversy-fraught work that underwent a court case under the U.S. sodomy laws. With Brion Gysin, he also popularized the literary cut-up technique in works such as The Nova Trilogy (1961–64).

In 1983, Burroughs was elected to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, and in 1984 was awarded the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by France.[2] Jack Kerouac called Burroughs the "greatest satirical writer since Jonathan Swift",[3] a reputation he owes to his "lifelong subversion"[1] of the moral, political and economic systems of modern American society, articulated in often darkly humorous sardonicism. J. G. Ballard considered Burroughs to be "the most important writer to emerge since the Second World War", while Norman Mailer declared him "the only American writer who may be conceivably possessed by genius".[3]

Burroughs had one child, William Seward Burroughs III (1947–1981), with his second wife Joan Vollmer. He died at his home in Lawrence, Kansas, after suffering a heart attack in 1997.

Contents

Early life and education

William S. Burroughs birthday

Burroughs was born in 1914, the younger of two sons born to Mortimer

Perry Burroughs (June 16, 1885 – January 5, 1965) and Laura Hammon Lee

(August 5, 1888 – October 20, 1970). The Burroughses were a prominent

family of English ancestry in St. Louis, Missouri. His grandfather, William Seward Burroughs I, founded the Burroughs Adding Machine company, which evolved into the Burroughs Corporation. Burroughs' mother was the daughter of a minister whose family claimed to be related to Robert E. Lee. His maternal uncle, Ivy Lee,

was an advertising pioneer later employed as a publicist for the

Rockefellers. His father ran an antique and gift shop, Cobblestone

Gardens; first in St. Louis, then in Palm Beach, Florida.

As a boy, Burroughs lived on Pershing Ave. in St. Louis's Central West End. He attended John Burroughs School in St. Louis where his first published essay, "Personal Magnetism", was printed in the John Burroughs Review in 1929.[4] He then attended the Los Alamos Ranch School in New Mexico, which was stressful for him. The school was a boarding school for the wealthy, "where the spindly sons of the rich could be transformed into manly specimens".[5] Burroughs kept journals

documenting an erotic attachment to another boy. According to his own

account, he destroyed these later, ashamed of their content.[6]

Due to the repressive context where he grew up, and from which he fled,

that is, a "family where displays of affection were considered

embarrassing",[7]

he kept his sexual orientation concealed well into adulthood, when he

became a well known homosexual writer after the publication of Naked Lunch in 1959. Some[who?] say that he was expelled from Los Alamos after taking chloral hydrate in Santa Fe

with a fellow student. Yet, according to his own account, he left

voluntarily: "During the Easter vacation of my second year I persuaded

my family to let me stay in St. Louis."[6]

Harvard University

Burroughs finished high school at Taylor School in Clayton, Missouri, and in 1932, left home to pursue an arts degree at Harvard University, where he was affiliated with Adams House. During the summers, he worked as a cub reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch,

covering the police docket. He disliked the work, and refused to cover

some events, like the death of a drowned child. He lost his virginity in

an East St. Louis brothel that summer with a female prostitute he regularly patronized.[8] While at Harvard, Burroughs made trips to New York City and was introduced to the gay subculture there. He visited lesbian dives, piano bars, and the Harlem and Greenwich Village homosexual underground with Richard Stern, a wealthy friend from Kansas City.

They would drive from Boston to New York in a reckless fashion. Once,

Stern scared Burroughs so much, he asked to be let out of the vehicle.[9]

Burroughs graduated from Harvard in 1936. According to Ted Morgan's Literary Outlaw,

Burroughs's parents sold the rights to his grandfather's invention and had no share in the Burroughs Corporation. Shortly before the 1929 stock market crash, they sold their stock for $200,000 (equivalent to approximately $2,746,899 in today's funds[11]).[12]His parents, upon his graduation, had decided to give him a monthly allowance of $200 out of their earnings from Cobblestone Gardens, a tidy sum in those days. It was enough to keep him going, and indeed it guaranteed his survival for the next twenty-five years, arriving with welcome regularity. The allowance was a ticket to freedom; it allowed him to live where he wanted to and to forgo employment.[10]

Europe

After leaving Harvard, Burroughs's formal education ended, except for brief flirtations as a graduate student of anthropology at Harvard and as a medical student in Vienna, Austria. He traveled to Europe and became involved in Austrian and Hungarian Weimar-era LGBT culture;

he picked up young men in steam baths in Vienna, and moved in a circle

of exiles, homosexuals, and runaways. There, he met Ilse Klapper, a Jewish woman fleeing the country's Nazi government. The two were never romantically involved, but Burroughs married her, in Croatia,

against the wishes of his parents, to allow her to gain a visa to the

United States. She made her way to New York City, and eventually

divorced Burroughs, although they remained friends for many years.[13]

After returning to the U.S., he held a string of uninteresting jobs. In

1939, his mental health became a concern for his parents, especially

after he deliberately severed the last joint of his left little finger,

right at the knuckle, to impress a man with whom he was infatuated.[14] This event made its way into his early fiction as the short story "The Finger".

Beginning of the Beats

Burroughs enlisted in the U.S. Army early in 1942, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor brought the U.S. into World War II.

But when he was classified as a 1-A Infantry, not an officer, he became

dejected. His mother recognized her son's depression and got Burroughs a

civilian disability discharge—a release from duty based on the premise

he should have not been allowed to enlist due to previous mental

instability. After being evaluated by a family friend, who was also a

neurologist at a psychiatric treatment center, Burroughs waited five

months in limbo at Jefferson Barracks outside St. Louis before being

discharged. During that time he met a Chicago soldier also awaiting

release, and once Burroughs was free, he moved to Chicago and held a

variety of jobs, including one as an exterminator. When two of his friends from St. Louis, Lucien Carr, a University of Chicago student, and David Kammerer, Carr's admirer, left for New York City, Burroughs followed.

Joan Vollmer

| This section does not cite any references or sources. (March 2011) |

In 1944, Burroughs began living with Joan Vollmer Adams in an apartment they shared with Jack Kerouac and Edie Parker, Kerouac's first wife.[15] Vollmer Adams was married to a GI

with whom she had a young daughter, Julie Adams. Burroughs and Kerouac

got into trouble with the law for failing to report a murder involving Lucien Carr,

who had killed David Kammerer in a confrontation over Kammerer's

incessant and unwanted advances. This incident inspired Burroughs and

Kerouac to collaborate on a novel titled And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks,

completed in 1945. The two fledgling authors were unable to get it

published, but the manuscript was eventually published in November 2008

by Grove Press and Penguin Books.

During this time, Burroughs began using morphine and became addicted. He eventually sold heroin in Greenwich Village to support his habit.

Vollmer also became an addict, but her drug of choice was Benzedrine, an amphetamine

sold over the counter at that time. Because of her addiction and social

circle, her husband immediately divorced her after returning from the

war. Vollmer would become Burroughs’ common-law wife.

Burroughs was soon arrested for forging a narcotics prescription and

was sentenced to return to his parents' care in St. Louis. Vollmer's

addiction led to a temporary psychosis which resulted in her admission

to a hospital, and the custody of her child was endangered. Yet after

Burroughs completed his house arrest in St. Louis, he returned to New

York, released Vollmer from the psychiatric ward of Bellevue Hospital, and moved with her and her daughter to Texas. Vollmer soon became pregnant with Burroughs's child. Their son, William S. Burroughs, Jr., was born in 1947. The family moved briefly to New Orleans in 1948.

Mexico and South America

Burroughs fled to Mexico to escape possible detention in Louisiana's Angola state prison.

Vollmer and their children followed him. Burroughs planned to stay in

Mexico for at least five years, the length of his charge's statute of limitations. Burroughs also attended classes at the Mexico City College in 1950 studying Spanish, as well as "Mexican picture writing" (codices) and the Mayan language with R. H. Barlow.

In 1951, Burroughs shot and killed Vollmer in a drunken game of "William Tell"

at a party above the American-owned Bounty Bar in Mexico City. He spent

13 days in jail before his brother came to Mexico City and bribed

Mexican lawyers and officials to release Burroughs on bail while he

awaited trial for the killing, which was ruled culpable homicide.[16]

Vollmer’s daughter, Julie Adams, went to live with her grandmother, and

William S. Burroughs, Jr., went to St. Louis to live with his

grandparents. Burroughs reported every Monday morning to the jail in

Mexico City while his prominent Mexican attorney worked to resolve the

case. According to James Grauerholz,

two witnesses had agreed to testify that the gun had gone off

accidentally while he was checking to see if it was loaded, and the

ballistics experts were bribed to support this story.[17] Nevertheless, the trial was continuously delayed and Burroughs began to write what would eventually become the short novel Queer

while awaiting his trial. However, when his attorney fled Mexico after

his own legal problems involving a car accident and altercation with the

son of a government official, Burroughs decided, according to Ted Morgan,

to "skip" and return to the United States. He was convicted in absentia

of homicide and was given a two-year sentence which was suspended.[18]

Although Burroughs was writing before the shooting of Joan Vollmer,

this event marked him and, biographers argue, his work for the rest of

his life.[19]

After leaving Mexico, Burroughs drifted through South America for several months, looking for a drug called yagé, which promised the user telepathy. A book composed of letters between Burroughs and Ginsberg, The Yage Letters, was published in 1963 by City Lights Books.

Beginning of literary career

Burroughs later said that shooting Vollmer was a pivotal event in his life, and one which provoked his writing:

I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan's death, and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing. I live with the constant threat of possession, and a constant need to escape from possession, from control. So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a life long struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.[20]

Yet he had begun to write in 1945. Burroughs and Kerouac collaborated on And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, a mystery novel loosely based on the Carr/Kammerer situation and that was left unpublished. Years later, in the documentary What Happened to Kerouac?,

Burroughs described it as "not a very distinguished work". An excerpt

of this work, in which Burroughs and Kerouac wrote alternating chapters,

was finally published in Word Virus,[21] a compendium of William Burroughs's writing that was published by his biographer after his death in 1997.

Before Vollmer died, Burroughs had largely completed his first two novels in Mexico, although Queer was not published until 1985. Junkie was written at the urging of Allen Ginsberg, who was instrumental in getting the work published, even as a cheap mass-market paperback.[22] Ace Books published the novel in 1953 as part of an Ace Double under the pen name William Lee, retitling it Junkie: Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict (it was later republished as Junkie or Junky).[22]

Tangier

During 1953, Burroughs was at loose ends. Due to legal problems, he

was unable to live in the cities towards which he was most inclined. He

spent time with his parents in Palm Beach, Florida, and New York City with Allen Ginsberg. When Ginsberg refused his romantic advances,[23] Burroughs went to Rome to meet Alan Ansen on a vacation financed from his parents' continuing support. When he found Rome and Ansen’s company dreary, and inspired by Paul Bowles' fiction, he decided to head for Tangier, Morocco.[24]

In a home owned by a known procurer of homosexual prostitutes for

visiting American and English men, he rented a room and began to write a

large body of text that he personally referred to as Interzone.[25]

Burroughs lived in Tangier for several months before returning to the

United States where he suffered a combination of personal indignities

and financial problems. Allen Ginsberg was at the time in California and

refused to see him. A. A. Wyn, the publisher of Junkie, was not forthcoming with his royalties. Burroughs’ parents were threatening to cut off his allowance.[citation needed]

To Burroughs, all signs directed a return to Tangier, a city where

drugs were freely available and where financial support from his family

would continue. He realized that in the Moroccan culture he had found an

environment that synchronized with his temperament and afforded no

hindrances to pursuing his interests and indulging in his chosen

activities. In 1950, Robert Ruark had described the unbridled tenor of

the Moroccan city in his syndicated column. Compared to Tangier, Ruark

wrote, “Sodom was a church picnic and Gomorrah a convention of Girl

Scouts.” The misogyny of the social structure also appealed to

Burroughs’ innate distrust and fear of women. In Tangier, the

ubiquitously veiled and shrouded woman loudly broadcast the subservient

female role.[26]

He left for Tangier in November 1954 and spent the next four years there working on the fiction that would later become Naked Lunch, as well as attempting to write commercial articles about Tangier. He sent these writings to Ginsberg, his literary agent for Junkie, but none were published until 1989 when Interzone, a collection of short stories, was published. Under the strong influence of a marijuana confection known as majoun and a German-made opioid called Eukodol,

Burroughs settled in to write. Eventually, Ginsberg and Kerouac, who

had traveled to Tangier in 1957, helped Burroughs type, edit, and

arrange these episodes into Naked Lunch.[27]

Naked Lunch

Further information: Naked Lunch

Whereas Junkie and Queer were conventional in style, Naked Lunch was his first venture into a non-linear style. After the publication of Naked Lunch, a book whose creation was to a certain extent the result of a series of contingencies, Burroughs was exposed to Brion Gysin's cut-up technique at the Beat Hotel in Paris in September 1959. He began slicing up phrases and words to create new sentences.[28]

At the Beat Hotel Burroughs discovered "a port of entry" into Gysin's

canvases: "I don't think I had ever seen painting until I saw the

painting of Brion Gysin."[29]

The two would cultivate a long-term friendship that revolved around a

mutual interest in artworks and cut-up techniques. Scenes were slid

together with little care for narrative. Perhaps thinking of his crazed physician, Dr. Benway, he described Naked Lunch as a book that could be cut into at any point. Although not considered science fiction, the book does seem to forecast—with eerie prescience—such later phenomena as AIDS, liposuction, autoerotic fatalities, and the crack pandemic.[30]

David Woodard and Burroughs standing in front of a dreamachine invented by Brion Gysin; Burroughs collaborated with Gysin in popularizing the literary cut-up technique, with which he wrote The Soft Machine, The Ticket That Exploded, and Nova Express.

Excerpts from Naked Lunch were first published in the United States in 1958. The novel was initially rejected by City Lights Books, the publisher of Ginsberg's Howl; and Olympia Press publisher Maurice Girodias,

who had published English-language novels in France that were

controversial for their subjective views of sex and anti-social

characters. But Allen Ginsberg worked to get excerpts published in Black Mountain Review and Chicago Review in 1958. Irving Rosenthal, student editor of Chicago Review, a quarterly journal partially subsidized by the university, promised to publish more excerpts from Naked Lunch, but he was fired from his position in 1958 after Chicago Daily News columnist Jack Mabley called the first excerpt obscene. Rosenthal went on to publish more in his newly created literary journal Big Table No. 1;

however, these copies elicited such contempt, the editors were accused

of sending obscene material through the United States Mail by the United States Postmaster General,

who ruled that copies could not be mailed to subscribers. New York

critic John Ciardi did manage to get a copy and wrote a positive review

of the work, prompting a telegram from Allen Ginsberg praising the

review.[31] This controversy made Naked Lunch interesting to Girodias again, and he published the novel in 1959.[citation needed]

After the novel was published, it slowly became notorious across

Europe and the United States, garnering interest from not just members

of the counterculture of the 1960s, but also literary critics such as Mary McCarthy. Once published in the United States, Naked Lunch was prosecuted as obscene by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, followed by other states. In 1966, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

declared the work "not obscene" on the basis of criteria developed

largely to defend the book. The case against Burroughs's novel still

stands as the last obscenity trial against a work of literature—that is,

a work consisting of words only, and not including illustrations or

photographs—prosecuted in the United States.

The "Word Hoard", the collection of manuscripts that produced Naked Lunch, also produced the later works The Soft Machine (1961), The Ticket That Exploded (1962), and Nova Express

(1963). These novels feature extensive use of the cut-up technique

which influenced all of Burroughs' subsequent fiction to a degree.

During Burroughs' friendship and artistic collaborations with Brion

Gysin and Ian Sommerville,

the technique was combined with images, Gysin's paintings, and sound,

via Somerville's tape recorders. Burroughs was so dedicated to the

cut-up method that he often defended his use of the technique before

editors and publishers, most notably Dick Seaver at Grove Press in the 1960s[32] and Holt, Rinehart & Winston

in the 1980s. The cut-up method, because of its random or mechanical

basis for text generation, combined with the possibilities of mixing in

text written by other writers, deemphasizes the traditional role of the

writer as creator or originator of a string of words, while

simultaneously exalting the importance of the writer's sensibility as an

editor. In this sense, the cut-up method may be considered as analogous

to the collage method in the visual arts.

Paris and the "Beat Hotel"

Burroughs moved into a rundown hotel in the Latin Quarter of Paris in 1959 when Naked Lunch was still looking for a publisher. Tangier,

with its easy access to drugs, small groups of homosexuals, growing

political unrest, and odd collection of criminals, had become

increasingly unhealthy for Burroughs.[33] He went to Paris to meet Ginsberg and talk with Olympia Press. In so doing, he left a brewing legal problem, which eventually transferred itself to Paris. Paul Lund,

a British former career criminal and cigarette smuggler whom Burroughs

met in Tangier, was arrested on suspicion of importing narcotics into

France. Lund gave up Burroughs, and some evidence implicated Burroughs

in the possible importation of narcotics into France. Once again, the

man faced criminal charges, this time in Paris for conspiracy to import

opiates, when the Moroccan authorities forwarded their investigation to

French officials. Yet it was under this impending threat of criminal

sanction that Maurice Girodias published Naked Lunch; the

publication helped in getting Burroughs a suspended sentence, since a

literary career, according to Ted Morgan, is a respected profession in

France.

The "Beat Hotel" was a typical European-style rooming house

hotel, with common toilets on every floor, and a small place for

personal cooking in the room. Life there was documented by the

photographer Harold Chapman, who lived in the attic room. This shabby, inexpensive hotel was populated by Gregory Corso, Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky for several months after Naked Lunch

first appeared. The actual process of publication was partly a function

of its "cut-up" presentation to the printer. Girodias had given

Burroughs only ten days to prepare the manuscript for print galleys, and

Burroughs sent over the manuscript in pieces, preparing the parts in no

particular order. When it was published in this authentically random

manner, Burroughs liked it better than the initial plan. International

rights to the work were sold soon after, and Burroughs used the $3,000

advance from Grove Press to buy drugs (equivalent to approximately $24,271 in today's funds[11]).[34] Naked Lunch was featured in a 1959 Life magazine cover story, partly as an article that highlighted the growing Beat literary movement.

During this time Burroughs found an outlet for material otherwise rendered unpublishable in Jeff Nuttall's My Own Mag.[citation needed]

The London years

Burroughs left Paris for London in 1966 to take the cure again with

Dr. Dent, a well-known English medical doctor who spearheaded a

reputedly painless heroin withdrawal treatment using the drug apomorphine.[35] Keith Richards and Anita Pallenberg would take this same cure in 1971, with Dr. Dent's nurse, Smitty.[36]

Dent's apomorphine cure was also used to treat alcoholism, although it

was held by several people who undertook it to be no more than

straightforward aversion therapy. Burroughs however was convinced.

Following his first cure, he wrote a detailed appreciation of

apomorphine and other cures, which he submitted to The British Journal of Addiction (Vol. 53, 1956) under the title "Letter From A Master Addict To Dangerous Drugs"; this letter is appended to many editions of Naked Lunch.

Though he ultimately relapsed, Burroughs ended up working out of

London for six years, traveling back to the United States on several

occasions, including one time escorting his son to the Lexington Narcotics Farm and Prison after the younger Burroughs had been convicted of prescription fraud in Florida. In the "Afterword" to the compilation of his son's two previously published novels Speed and Kentucky Ham,

Burroughs writes that he thought he had a "small habit" and left London

quickly without any narcotics because he suspected the U.S. customs

would search him very thoroughly on arrival. He claims he went through

the most excruciating two months of opiate withdrawal while seeing his

son through his trial and sentencing, traveling with Billy to Lexington, Kentucky from Miami to ensure his son entered the hospital he once spent time in as a volunteer admission.[37] Earlier Burroughs revisited St. Louis, Missouri, taking a large advance from Playboy to write an article about his trip back to St. Louis, one that was eventually published in The Paris Review, after Burroughs refused to alter the style for Playboy's publishers. In 1968 Burroughs joined Jean Genet, John Sack, and Terry Southern in covering the 1968 Democratic National Convention for Esquire

magazine. Southern and Burroughs, who had first become acquainted in

London, would remain lifelong friends and collaborators. In 1972,

Burroughs and Southern unsuccessfully attempted to adapt Naked Lunch for the screen in conjunction with American game-show producer Chuck Barris.[38]

Burroughs supported himself and his addiction by publishing pieces in

small literary presses. His avant-garde reputation grew internationally

as the hippie counterculture discovered his earlier works. He developed

a close friendship with Anthony Balch and lived with a young hustler

named John Brady who continuously brought home young women despite

Burroughs' protestations. In the midst of this personal turmoil,

Burroughs managed to complete two works: a novel written in screen play format, The Last Words of Dutch Schultz (1969); and the traditional prose-format novel The Wild Boys (1971).

In the 1960s, Burroughs joined and then left the Church of Scientology.

In talking about the experience, he claimed that the techniques and

philosophy of Scientology helped him and that he felt that further study

into Scientology would produce great results.[39] He was skeptical of the organization itself, and felt that it fostered an environment that did not accept critical discussion.[40] His subsequent critical writings about the church and his review of Inside Scientology by Robert Kaufman led to a battle of letters between Burroughs and Scientology supporters in the pages of Rolling Stone magazine.

Return to U.S.

In 1974, concerned about his friend's well-being, Allen Ginsberg gained for Burroughs a contract to teach creative writing at the City College of New York.